Kings, queens and bishops are part of the solution to Australia’s 21st century economic challenges, but not the monarchical or religious variety — chess, if more widely played, has the potential to boost innovation and economic growth, according to one avid player.

Management consultant and former political adviser John Adams. ‘Chess improves cognitive ability and that in turn has strong relationship with economic growth’.

Fresh from espousing the economic virtues of chess at an international Chess Conference in London, John Adams believes Australia’s falling educational outcomes and sputtering productivity growth could be helped by a greater focus on playing chess in schools. “I’m not saying it’s a silver bullet but there is definitely a public policy role for chess that policy makers shouldn’t discount,” he says, pointing to a range of studies that show chess playing has improved students’ maths and problem-solving abilities.

A management consultant and former political adviser to cabinet secretary senator Arthur Sinodinos, Mr Adams is also government relations director at the Australian Chess Federation. He says Australia’s “weak chess culture” is holding back its economic potential.

“Chess improves cognitive ability and that in turn has strong relationship with human capital and economic growth,” Mr Adams says, noting that a range of countries such as Hungary and Denmark had made chess mandatory or at least optional in primary and high school. “Armenia is leading country where the president is also the president of chess association as well.”

The board game, whose modern rules emerged in Europe at least 500 years ago, forces players to think strategically in order to “check mate”, or defeat, their opponents and can last hours or even days. The Soviet Union once boasted of its chess prowess to signal its superiority at mathematics.

A former chess champion himself from Kanahooka High in Wollongong in southern NSW, Mr Adams credits his chessplaying as a student with helping him succeed at 4-unit maths — the highest level — in year 12.

“We know that if you put a mouse in a complex maze their brains become more developed — and humans, if they are challenged mentally, will develop better mental capacities.”

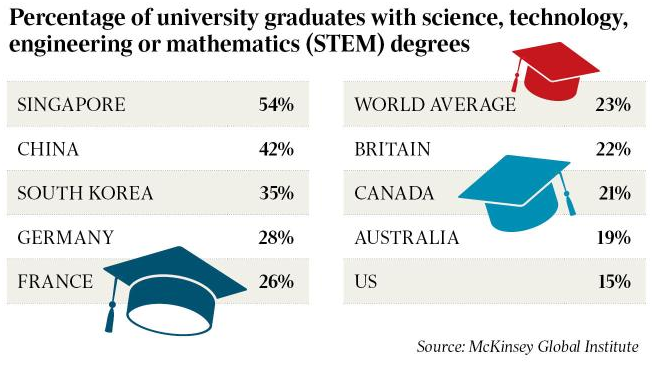

Mr Adams said countries’ economic success in the 21st century would depend on their ability to harness the intellectual talents of their workforces, to innovate and solve intellectual problems in contrast to the physical work that dominated production in the 20th century.

Australia’s standing in OECD league tables that measure students’ aptitude across countries has plummeted over the past 15 years, from 6th to 19th in maths, 7th to 16th in science and 4th to 13th in reading literacy.

“We’re so focused on the budget etc, but we are ignoring a major structural problem in our education system that will have a tremendous impact on our human capital,’’ he says.

The Turnbull government’s recent suite of policies to boost innovation entails $1 billion of tax breaks for investors and extra funding for research, but overlooks the benefit of chess.

Mr Adams says attempts in Australia thus far to attract public interest in chess had failed because they focused exclusively on the educational benefits rather than the important link to economic growth and development.

Original article: The Australian, January 11, 2016 12:00AM

Author: Adam Creighton